Over the past decade, Apple has made many decisions that have shaped the landscape of device repairability. From the introduction of proprietary screws and security features to more recent efforts supporting the “right to repair” movement, Apple’s actions have significantly impacted users, technicians, and the repair industry as a whole. While much of this has been met with criticism, there is a silver lining. In a turn of events, Apple has recently shown support for repair legislation—an unexpected shift from their previous stance.

In this article, we’ll explore how Apple’s design choices have shaped repairability, from their first screw to their recent repair policy changes. By understanding this evolution, you’ll have a clearer picture of the challenges faced when repairing Apple devices—and why some problems aren’t always caused by bad repair work.

The Beginning: The Pentalobe Screw and User-Replaceable Batteries

Apple’s journey toward restricting repairability arguably began in 2009 with the introduction of the pentalobe screw. First seen on the battery of that year’s MacBook Pro, it was the first sign of Apple locking users out of their own repairs. At the time, Apple shifted from using traditional screws, like the Philips head, to this five-pointed design that required a special screwdriver. It wasn’t just a move to prevent user repairs—it was the start of Apple’s drive to make devices harder to open.

By 2011, the pentalobe screw had found its way into the iPhone 4, cementing Apple’s commitment to proprietary hardware. Unlike other screw types, the pentalobe design is similar to a Torx screw but just different enough that a Torx driver could easily strip the screw, making repairs more difficult.

Software Lockdowns: The iPhone 3GS and Software Signing

2013 saw Apple’s next step towards limiting repairs and modifications with the introduction of the iPhone 3GS and the iPhone’s software signing server. This move prevented users from downgrading to older iOS versions, essentially tying every device to the latest software updates. While this was a tactic to combat jailbreaking, it also played into Apple’s long-term strategy—allowing them to slow down older devices via software updates. This controversial move, later admitted by Apple in 2017, raised questions about the company’s intentions and the repairability of older devices.

The Era of Rivets and Glue: 2012-2015

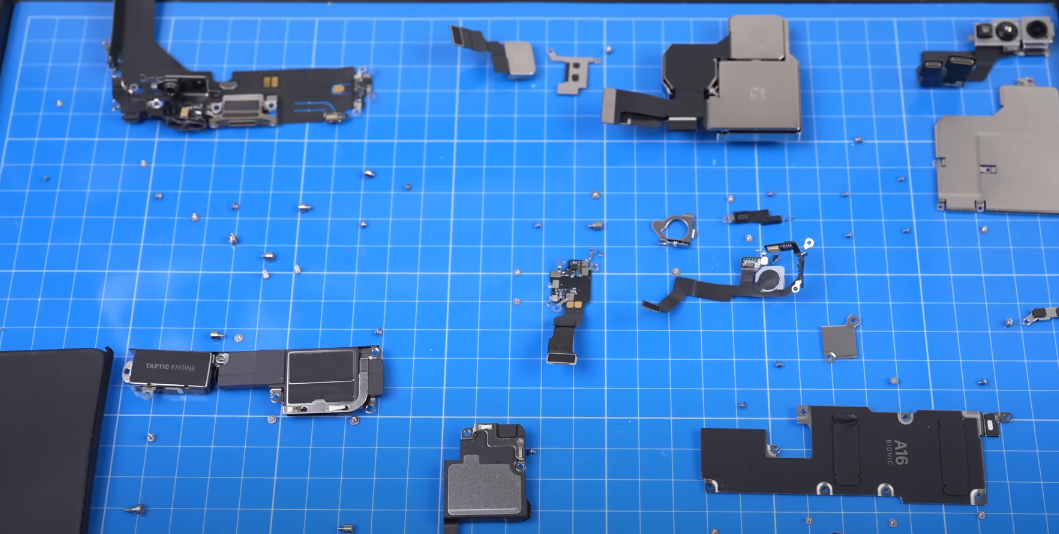

In 2012, Apple unveiled the retina MacBook Pro, introducing another repair hurdle: riveted keyboards. The keyboard was no longer attached with screws but rivets, making it nearly impossible to replace individually without damaging the device. This design choice also led to a situation where Apple could only replace the keyboard as part of the entire top case, complete with a new battery and other internal components.

Along with rivets, glued batteries made their debut. What once were user-replaceable, screw-in batteries were now glued into place, making them difficult—and sometimes impossible—to remove without damaging the rest of the device. These changes came as part of Apple’s thinness obsession, which prioritized slim designs at the expense of upgradeability and repairability.

Soldered Components: A Shift Towards Non-Upgradable Devices

Apple’s move toward soldering crucial components became more pronounced in 2015 with the redesign of their MacBook laptops. Soldered RAM and soldered storage became the norm, starting with the 12-inch MacBook and quickly spreading to the MacBook Pro, MacBook Air, and eventually even the iMac and Mac Mini. This shift marked a significant reduction in the ability to upgrade or replace these parts. If the RAM or storage failed, users would have to replace the entire motherboard—an expensive and often impractical solution.

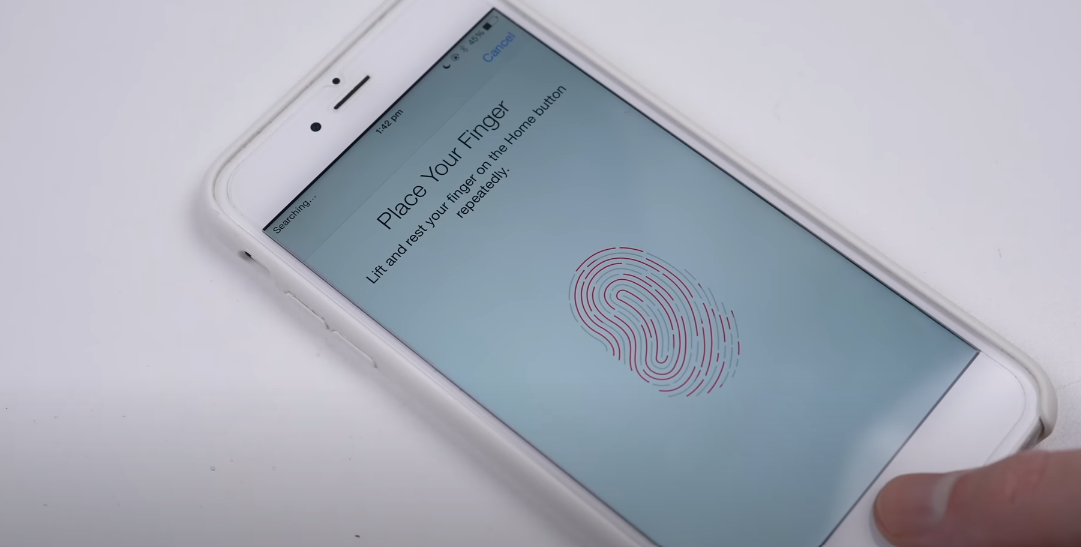

Touch ID, True Tone, and More: Tying Hardware to Software

From 2013 to 2017, Apple began incorporating software lockouts tied to specific components, further complicating repairs. In 2013, the Touch ID sensor was introduced, paired to each device’s motherboard, meaning if you replaced the sensor, it would no longer function correctly. This was not just a security feature; it was a clear attempt to restrict third-party repairs and modifications.

By 2017, True Tone on the iPhone 8 was introduced, which used a color-shifting software algorithm to adjust the display based on ambient lighting conditions. If the display was replaced, True Tone would be disabled unless the serial number from the old display was transferred to the new one. Apple made this process even more challenging by encrypting the display’s serial number, forcing technicians to jump through hoops to restore the feature.

Face ID and the Back Glass Nightmare

The iPhone X in 2017 introduced Face ID, which was paired to each device’s front camera and other sensors. A repair or replacement of these components would result in Face ID becoming disabled, even if the replacement part was from a working device. The iPhone 8 and X also marked the arrival of glass rear panels. While this made wireless charging possible, it also meant stronger glue, requiring lasers to remove the back glass. It wasn’t until the iPhone 14 and 15 Pro that Apple would introduce removable back glass, making it easier to repair or replace.

The “Battery Gate” Scandal: Software Manipulation

In 2017, Apple admitted to intentionally slowing down older devices as their batteries aged. While this was intended to prevent unexpected shutdowns due to degraded batteries, Apple did not disclose this behavior to consumers at the time. This raised major concerns about Apple’s repair policies and whether the company was intentionally pushing users to upgrade rather than repair their devices.

As part of the fallout from Battery Gate, Apple introduced battery health monitoring in later versions of iOS, allowing users to check their battery’s condition. However, this feature became another barrier to third-party repairs. Replacing an iPhone battery with an unauthorized part would trigger a message in Settings, warning that the new battery was not genuine. The same applied to displays, further locking down repairs.

The Mac Pro and Proprietary SSDs

In 2019, Apple released the Mac Pro, which came with paired SSDs. These drives, while physically removable, were still tied to the machine by a proprietary configuration, meaning users could not easily upgrade or replace them without purchasing Apple’s expensive, proprietary drives. This was also the case with the Mac Studio, which also made it impossible to upgrade to larger SSDs unless using Apple-approved storage.

The Shift Towards Self-Repair

In 2021, Apple took a significant step toward addressing repairability concerns with the launch of their Self-Repair Program. While the initiative gave customers access to official parts, tools, and repair guides, the program had significant drawbacks. The cost of parts was often close to what Apple would charge for repairs, making self-repair less cost-effective for many users.

More importantly, Apple still retains control over repairs, requiring customers to buy parts directly from Apple in order to retain full functionality. If users purchased third-party parts, Apple’s software could prevent them from functioning as intended.

A Ray of Hope: Support for the “Right to Repair”

Despite years of aggressively controlling repair, Apple has recently shown support for right to repair legislation. In a surprising shift, Apple backed California’s right to repair bill, which would allow consumers and independent repair shops to access the tools and parts needed to repair devices. This legislation applies to devices sold after July 1, 2021, and Apple says it will honor this provision across the United States. This change signals that Apple may finally be willing to allow more flexibility when it comes to repairing their devices.

Conclusion: Repairability and the Road Ahead

Apple’s approach to repairability has been a mixed bag—while some decisions have made repairs more difficult or expensive, the company’s recent stance on repair legislation shows signs of progress. Although we’re still far from a perfect repair ecosystem, Apple’s backing of repair rights could lead to positive changes for both consumers and the repair industry.

If you’ve faced challenges in repairing your Apple device, whether it’s due to software lockouts, proprietary screws, or glued-in components, now you have a better understanding of how these issues came to be—and how they might evolve moving forward. The right to repair is a battle still being fought, but with recent developments, there’s hope for a future where repairs are more accessible to everyone.

Thank you for reading, and be sure to check out my other videos and articles on tech repair and restoration. If you’re in the market for used devices, feel free to browse my online store linked below. Until next time!